Description

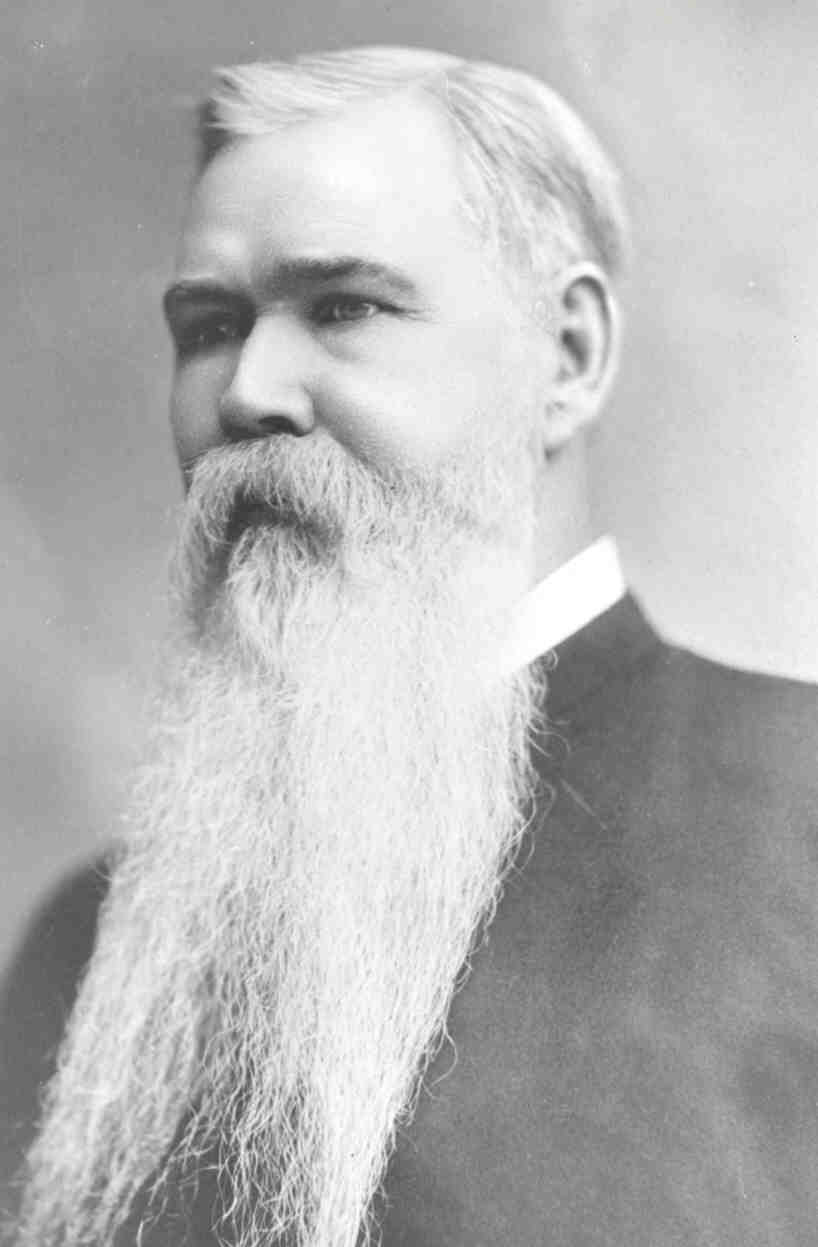

An Interpretation of the English Bible Volume V

THE HEBREW

MONARCHY

by

B. H. CARROLL

Late President of Southwestern Baptist

Theological Seminary, Fort Worth, Texas

Edited by

J. B. Cranfill

Contents

I AUTHOR’S INTRODUCTION. 4

II THE EARLY LIFE OF SAMUEL. 11

III THE FALL OF THE HOUSE OF ELI, AND THE RISE OF SAMUEL 25

IV THE SCHOOLS OF THE PROPHETS. 35

V SAMUEL AND THE MONARCHY, AND HIS VINDICATION AS JUDGE 45

VI SAUL, THE FIRST KING. 55

VII SAUL, THE FIRST KING (CONTINUED) 65

VIII THE PASSING OF SAUL AND HIS DYNASTY. 73

IX SAUL’S UNPARDONABLE SIN, AND ITS PENALTY. 84

X DAVID CHOSEN AS SAUL’S SUCCESSOR, AND HIS INTRODUCTION TO THE COURT OF SAUL 96

XI THE WAR BETWEEN LOVE AND HATE – THE STORY OF A LOST SOUL 111

XII SAUL’S MURDEROUS PURSUIT OF DAVID. 123

XIII DAVID AND HIS INDEPENDENT ARMY; THE END. 133

XIV ZIKLAG, ENDOR, AND GILBOA. 143

XV HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION TO 2 SAMUEL AND 1 CHRONICLES 156

XVI DAVID, KING OF JUDAH AT HEBRON, AND THE WAR WITH THE HOUSE OF SAUL 166

XVII DAVID MADE KING OVER ALL ISRAEL, AND THE CAPTURE OF JERUSALEM FOR A CAPITAL. 174

XVIII THE WARS OF DAVID. 184

XIX THREE DARK EVENTS OF DAVID’S CAREER. 194

XX BRINGING UP THE ARK AND THE ESTABLISHMENT OF A CENTRAL PLACE OF WORSHIP 211

XXI DAVID’S KINDNESS TOWARD JONATHAN’S SON; BIRTH OF SOLOMON; FAMILY TROUBLES; THE THREE YEARS OF FAMINE. 222

XXII THE SIN OF NUMBERING THE CHILDREN OF ISRAEL, ITS PENALTY, AND THE HISTORY OF ABSALOM.. 230

XXIII DEATH OF ABSALOM; PREPARATION FOR SOLOMON’S ACCESSION, AND THE BUILDING OF THE TEMPLE. 238

XXIV THE ARMY; CIVIL ORGANIZATION; INTERNATIONAL COMMERCE; RELIGIOUS ORGANIZATION. 247

XXV BOOKS ON THE REIGN OF SOLOMON; THE EMPIRE OF SOLOMON; SOLOMON’S INHERITANCE FROM HIS FATHER. 255

XXVI SOLOMON’S ACCESSION, MARRIAGE, DREAM, AND REMARKABLE WISDOM 267

XXVII THE ANALYSIS OF SOLOMON’S WISDOM.. 279

XXVIII THE WORKS OF SOLOMON. 290

XXIX DEDICATION OF THE TEMPLE. 301

XXX THE FALL AND END OF SOLOMON. 314

I AUTHOR’S INTRODUCTION

The general theme of this section is “The Hebrew Monarchy.” The textbook is Crockett’s Harmony of Samuel; Kings and Chronicles. The collateral textbook is Wood’s Hebrew Monarchy. The best and most convenient commentary on Samuel is Kirkpatrick’s, in the “Cambridge Bible.” Other good textbooks on Samuel and his times are: Edersheim’s “History of Israel,” Vol. IV; Dean’s Samuel and Saul; Hengstenberg’s Kingdom of God in the Old Testament, Vol. II; Hengstenberg’s Christology of the Old Testament, Vol. 1; Stanley’s Jewish Church; Geikie’s Hours with the Bible; Geikie’s Bible Characters – Eli, Samuel, Saul; Sampey’s Syllabus; Josephus. A good special commentary on Chronicles is Murphy’s.

First Chronicles 8-10 parallels 1 Samuel, and the important distinctions between Samuel and Kings on the one part, and Chronicles on the other part, are:

1. In the time of composition and in the authors, Samuel and Kings were written by authors contemporary with the events, but Chronicles was all compiled by Ezra after the downfall of the monarchy.

2. The purpose was different. Samuel and Kings aim to give a continuous history by contemporaneous authors, of all Israel from the establishment of the kingdom, first showing the transition from Judges to Kings, then the division of the kingdom, then the history of the kingdoms to the downfall of each, a period of five hundred years, all continuous history by contemporaneous authors. But the purpose of Chronicles is unique. Ignoring the Northern Kingdom, it is designed to show merely the genealogy and history of the Davidic line alone, in which the national union is preserved, and, commencing with Adam, it shows the persistence of national life after the downfall of the monarchy. Its viewpoint is the restoration after the captivity by Babylon. And while, indeed, the compiler uses the material of contemporaneous historians, or material of historians contemporaneous with the events as they came to pass, yet it is used as a retrospect.

3. Chronicles is a new and different beginning of Jewish history, rooting in Genesis, and becomes the introduction of all exile and post exile Old Testament books) and for the uninspired books of the inter-Biblical period, and hence is a preparation for the coming Messiah in the Davidic line.

4. Hence the first seven chapters of Chronicles parallel Old Testament books prior to Samuel, and its last paragraph goes beyond Kings in showing the connection with post-exile history.

5. While it is proper to use Chronicles in the Harmony with Samuel and Kings, one who studies Chronicles in the Harmony only, can never get its true conception.

As to the title, “Samuel,” to the two books which bear that name, the following explanation is apropos:

1. In the Jewish enumeration the two books are one. A note at the end of 2 Samuel in the Hebrew Bible still treats the two books as one, and Eusebius, the great church historian, quotes Origen to the effect that the Jews of his day counted the books one. Josephus so counts them.

2. The meaning of the title is twofold: (a) Up to the death of Samuel it means the author of the book, and (b) as applied to the whole book it means the principal hero of the story up to the time of David.

1. Considering the history and the sources of the material, we learn from 1 Chronicles 29:29 that the history of the reign of David is ascribed to three prophets, Samuel, Nathan, and Gad; and from other passages in Chronicles we learn that other prophets took up the story. So far as the scope of I and 2 Samuel extends we may well say that the writers were Samuel, Nathan, and Gad, i.e., Samuel up to 1 Samuel 25, then Nathan and Gad.

2. First Chronicles 27:24 tells us of the state records of David’s reign, and from these records may have been obtained such matter as appears in 2 Samuel 8:16-18; 20:23-26; 23: 8-39.

3. In 1 Samuel 10:25 we learn that the charter of the kingdom is expressly said to have been written by Samuel.

4. It is very probable that the national poetic literature furnished Hannah’s song (1 Sam. 2:1-10); David’s lament for Abner (2 Sam. 3:33-34); David’s Thanksgiving (2 Sam. 22, which is also the same as Psalm 18); the last words of David (2 Sam. 23:1-7). David’s lament for Saul and Jonathan (2 Sam. 1:18-27) is expressly said to be taken from the book of Jasher.

Certain passages in the book itself bear on the date of the compilation in its present form:

1. There is an explanation in 1 Samuel 9:9 of old terms which would be necessary, for the terms were not in use when the book was compiled.

2. There is a reference to obsolete customs in 2 Samuel 13:18.

3. The phrase “unto this day” is repeated seven times: 1 Samuel 5:5; 6:18; 27:6; 30:25; 2 Samuel 4:3; 6:8; 18:18.

4. Second Samuel 5:5 refers to the whole reign of David.

5. In the Septuagint, but not in the Hebrew, there are references extending to Rehoboam, Solomon’s son.

6. In 1 Samuel 27:6 mention of the kings of Judah seems to imply that the divisions of the kingdom in Rehoboam’s day had taken place. The conclusion as to the date of the present form is that is was compiled soon after the division of the kingdom. The canonicity of Samuel has never been questioned. It is remarkably accurate, and in every way reliable. Each part is the language of the contemporaneous historian who was an eye witness of the scenes, though there are some parts difficult to harmonize, which will be noticed particularly as they come up.

The materials for the text are the Hebrew Manuscript, and the versions, to wit: The Septuagint; the Chaldean, or Aramaic; and the Vulgate. Our manuscripts of the Septuagint are mainly the Alexandrian Manuscript of the fifth century A.D., and the Vatican Manuscript of the fourth century. The Alexandrian Manuscript conforms most nearly to the Hebrew text, there being an important variation in the Vatican Manuscript from the Hebrew text that will be subsequently noted. The Chaldean, or Aramaic version, commonly known as the Targum of Jonathan Ben Uzziel, is more a commentary or paraphrase than a translation, and that, too, of the later Jews. In the third note to the Appendix of 2 Samuel in the “Cambridge Bible” we find in this Targum quite a remarkable addition to Hannah’s Song, ascribing to her a prophecy that touches the destruction of the Philistines; the descendants of Samuel, who form a part of the Davidic choir, and concerns Sennacherib and Nebuchadnezzar, Greece, Haman, and Rome. For this prophecy, there is no inspired foundation.

Dr. Sampey, of the Louisville Seminary, says that the text of this section needs editing more than any other part of the Bible, and there are some peculiarities of the text which we will now take up:

1. Certain passages exist in duplicate, all of them in 2 Samuel except 1 Samuel 31, which is the same as 1 Chronicles 10: 1-12.

2. There are others remarkably similar; for example, compare the account in chapters 23:19 to 24:22 with chapter 26.

3. The Septuagint in the Vatican Manuscript differs from the Alexandrian Manuscript and also from the Hebrew, in omitting a considerable part of chapters 17 and 18. The omission removes certain difficulties but creates others.

4. The narrative of the Witch of Endor raising the ghost or shade of Samuel (chap. 28) has provoked controversies in every age, and special attention will be given to that when we get to it.

5. In 1 Samuel 1:3 will be found an entirely new name for God. It is not found in any antecedent Old Testament book nor in many subsequent Old Testament books. The name is the Lord of Sabaoth, which means the Lord of Hosts. All of these peculiarities will be noted more particularly as we come to them.

The following is Dr. Kirkpatrick’s analysis of 1 Samuel:

I. The close of the period of the Judges, chapters 1-7.

1. The early life of Samuel, extending from 1:1 to 4:la.

2. The judgment of Eli and the loss of the Ark, 4:.lb-7:1.

3. The judicial life of Samuel, 7:2-17.

II. The foundation of the monarchy, chapters 8-31.

1. The appointment of the first king, chapters 8-10.

2. Saul’s reign unto his rejection, chapters 11-15.

3. Decline of Saul and rise of David, chapters 16-31.

QUESTIONS

1. What the general theme of this section?

2. What the textbook?

3. What the collateral textbook?

4. What the best and most convenient commentary on Samuel?

5. What other good textbooks on Samuel and his times?

6. What special commentary on Chronicles commended?

7. What part of 1 Chronicles parallels 1 Samuel?

8. What important distinctions between Samuel and Kings on the one part, and Chronicles on the other part?

9. What of the title, “Samuel,” to the two books which bear that name?

10. Who wrote the history, and what the sources of the material?

11. What passages in the book itself bear on the date of the compilation in its present form?

12. What the conclusion as to the date of the present form?

13. What of the canonicity of Samuel?

14. What of the accuracy and reliability of the history?

15. What can you say of the text of the book of Samuel?

16. What does Dr. Sampey say of the text?

17. What peculiarities of the text noted?

18. Whose analysis commented, and what its main divisions and subdivisions?

II THE EARLY LIFE OF SAMUEL

1 Samuel 1:1 to 4:1a and Harmony pages 62-66.

We omit Part I of the textbook, since that first part is devoted to genealogical tables taken from 1 Chronicles. That part of Chronicles is not an introduction to Samuel or Kings, but an introduction to the Old Testament books written after the Babylonian captivity. To put that in now would be out of place.

We need to emphasize the supplemental character of Chronicles. Our Harmony indeed will show from time to time in successive details the very important contributions of that nature in Chronicles not found in any form in the histories of Samuel and Kings, nor elsewhere in the Old Testament; but to appreciate the magnitude of this new matter we need to glance at it in bulk, not in detail, as its parts will come up later.

There are twenty whole chapters and parts of twenty-four other chapters in Chronicles occupied with matter not found in other books of the Bible. This is a considerable amount of new material, and is valuable on that account but it is still more valuable because it presents a new aspect of Hebrew history after the captivity. The following passages in Chronicles contain new matter: 1 Chronicles 2:18-55; 3:19-24;-4-9; 11:41-47; 12; 15:1-26; 2229; 2 Chronicles 6:40-42; 11:5-23; 12:4-8; 13:3-21; 14:3-15; 15:1-15; 16:7-10; 17-19; 20:1-30; 21:2-4, 11-19; 24:15-22; 25:5-10, 12-16; 26:5-20; 27:4-6; 28:5-25; 29:3-36; 30-31; 32:22-23; 26-31; 33:11-19; 34:3-7; 35:2-17,25; 36:11-23.

Whoever supposed that there was that much material in the book of Chronicles that could not be found anywhere else? One can study Chronicles as a part of a Harmony with Samuel and Kings, but if that were the only way it could be studied he would never get the true significance of it, as it is an introduction to all of the later Old Testament books. In the light of these important new additions, we not only see the introduction of all subsequent Old Testament books and also inter-Biblical books by Jews, but must note the transition in thought from a secular Jewish kingdom to an approaching spiritual messianic kingdom.

We thus learn that Old Testament prophecy is not limited to distinct utterances foretelling future events, but that the whole history of the Jewish people is prophetic; not merely in its narrative, but in its legislation, in its types, feasts, sabbaths, sacrifices, offerings; in its tabernacle and Temple, with all of their divinely appointed worship and ritual, and this explains why the historical books are classed as prophetic, not merely because prophets wrote them, which is true, but also because the history is prophetic.

In this fact lies one of the strongest proofs of the inspiration of the Old Testament books in all of their parts. The things selected for record, and the things not recorded, are equally forcible. The silence equals the utterance. This is characteristic of no other literature, and shows divine supervision which not only makes necessary every part recorded, but so correlates and adapts the parts as to make perfect literary and spiritual structure which demands a New Testament as a culmination.

Moreover, we are blind if we cannot see a special Providence preparing a leader for every transition in Jewish history. Just as Moses was prepared for deliverance from Egypt, and for the disposition of the law, so Samuel is prepared, not only to guide from a government by judges to a government by kings, but, what is very much more important, to establish a School of the Prophets – a theological seminary.

These prophets were to be the mouthpieces of God in speaking to kingly and national conscience, and for 500 years afterward, become the orators, poets, historians, and reformers of the nation, and so, for centuries, avert, postpone, or remedy, national disasters provoked by public corruption of morals and religion.

Counting great men as peaks of a mountain range, and sighting backward from Samuel to Abraham, only one peak, Moses, comes into the line of vision.

There are other peaks, but they don’t come up high enough to rank with Abraham, Moses, and Samuel. A list of the twelve best and greatest men in the world’s history must include the name of Samuel. When we come, at his death, to analyze his character and posit him among the great, other things will be said. Just now we are to find in his early life that such a man did not merely happen; that neither heredity, environment, nor chance produced him.

Samuel was born at Ramah, lived at Ramah, died at Ramah, and was buried at Ramah. Ramah is a little village in the mountains of Ephraim, somewhat north of the city of Jerusalem. It is right hard to locate Ramah on any present map of the Holy Land. Some would put it south, some north. It is not easy to locate like Bethlehem and Shiloh.

Samuel belonged to the tribe of Levi, but was not a descendant of Aaron. If he had been he would have been either a high priest or a priest. Only Aaron’s descendants could be high priests, or priests, but Samuel belonged to the tribe of Levi, and from 1 Chronicles 6 we may trace his descent. The tribe of Levi had no continuous landed territory like the other tribes, but was distributed among the other tribes. That tribe belonged to God, and they had no land assigned them except the villages in which they lived and the cities of the refuge, of which they had charge, and so Samuel’s father could be called an Ephrathite and yet be a descendant of the tribe of Levi – that is, he was a Levite living in the territory of Ephraim.

The bigamy of Samuel’s father produced the usual bitter fruit. The first and favorite wife had no children, so in order to perpetuate his name he took a second wife, and when that second wife bore him a large brood of children she gloried over the first wife, and provoked her and mocked at her for having no children, and it produced a great bitterness in Hannah’s soul. The history of the Mormons demonstrates that bitterness always accompanies a plurality of wives. I don’t see bow a woman can share a home or husband with any other woman.

We will now consider the attitude of the Mosaic law toward a plurality of wives, divorce, etc. In Deuteronomy 21:15-17 we see that the Mosaic law did permit an existing custom. It did not originate it nor command it, but it tolerated the universal custom of the times, a plurality of wives. From Deuteronomy 24:1-4, we learn that the law permitted a husband to get rid of a wife, but commanded him to give her a bill of divorcement. That law was not made to encourage divorcement, but to limit the evil and to protect the woman who would suffer under divorce. Why the law even permitted these things we see from Matthew 19:7-8. Our Saviour there tells us that Moses, on account of the hardness of their hearts, permitted a man to put away his wife. That is to say, that nation had just emerged from slavery, and the prevalent custom all around them permitted something like that, and because they were not prepared for an ideal law on the subject on account of the hardness of their hearts, Moses tolerated, without commending a plurality of wives or commanding divorce – both in a way to mitigate the evil, but when Jesus comes to give his statute on the subject he speaks out and says, “Whosoever shall put away his wife except for marital infidelity and marries again committeth adultery, and whosoever shall marry her that is put away committeth adultery.” A preacher in a recent sermon, as reported, discredited that part of Matthew because not found also in Mark. I have no respect for the radical criticism which makes Mark the only credible Gospel, or even the norm of the others. Nor can any man show one shred of evidence that it is so. I have a facsimile of the three oldest New Testament manuscripts. What Matthew says is there, and may not be eliminated on such principles of criticism.

The radical critics say that the Levitical part of the Mosaic law was not written by Moses, but by a priest in Ezekiel’s time, and that Israel had no central place of worship in the period of the judges, but this section shows that they did have a central place of worship at Shiloh, and the book of Joshua shows when Shiloh became the central place of worship. The text shows that they did come up yearly to this central place of worship, and that they did offer, as in the case of Hannah and Elkanah, the sacrifices required in Leviticus.

In Joshua 18:1 we learn that when the conquest was finished Joshua, himself, placed the ark of the covenant and the tabernacle at Shiloh, and constituted it the central place of worship. In this section we learn what disaster ended Shiloh as the central place of worship. The ark was captured, and subsequently the tabernacle was removed, and that ark and that tabernacle never got together again. In Jeremiah 7:12 we read: “But go ye now unto my place which was in Shiloh, where I caused my name to dwell at the first, and see what I did to it for the wickedness of my people Israel.” Jeremiah is using that history as a threat against Jerusalem, which in Jeremiah’s time was the central place of worship. His lesson was, “If you repeat the wickedness done in Samuel’s time God will do to your city and your home what he did to Shiloh.” It is important to know the subsequent separate history of the ark and the tabernacle, and when and where another permanent central place and house of worship were established. The Bible tells us every move that ark and that tabernacle made, and when, where, and by whom the permanent central place and house of worship were established.

Eli was high priest at Samuel’s birth. In those genealogical tables that we omitted from 1 Chronicles we see that Eli was a descendant of Aaron, but not of Eleazar, the eldest son; therefore, according to the Mosaic law, he ought never to have been high priest, but he was, and I will have something to say about that when the true line is established later. 1 Samuel 4, which comes in the next chapter, distinctly states that Eli judged Israel forty years, and he was likely a contemporary of Samson. But Eli, at the time we know him, is ninety-eight years old, and nearly blind. He was what we call a goodhearted man, but weak. That combination in a ruler makes him a curse. Diplomats tell us “a blunder is worse than a crime,” in a ruler. He shows his weakness in allowing his sons, Hophni and Phinehas, to degrade the worship of God. They were acting for him, as he was too old for active service. The most awful reports came to him about the infamous character of these sons, who occupied the highest and holiest office in a nation that belonged to God.

This section tells us that he only remonstrated in his weak way: “My sons, it is not a good report that I hear about you,” but that is all he did. As he was judge and high priest, why should he prefer his sons to the honor of God? Why did he not remove them from positions of trust and influence? His doom is announced in this section, and it is an awful one. God sent a special prophet to him and this is the doom. You will find it in chapter 2, commencing at verse 30: “Wherefore the Lord, the God of Israel, saith, I said indeed that thy house, and the house of thy father, should walk before me forever: but now the Lord saith, Be it far from me; for them that honor me I will honor, and they that despise me shall be lightly esteemed. Behold, the days come, that I will cut off thine arm, and the arm of thy father’s house, that there shall not be an old man in thine house. And thou shalt see an enemy in my habitation (Shiloh), in all the wealth which God shall give Israel: and there shall not be an old man among thy descendants forever. And the descendants of thine, whom I do not cut off from mine altar, shall live to consume thine eyes and grieve thine heart: and all the increase of thine house shall die in the flower of their age.”

Or as Samuel puts it to him, we read in chapter 3, commencing at verse 11: “And the Lord said unto Samuel, Behold I will do a thing in Israel, at which both the ears of every one that heareth it shall tingle. In that day I shall perform against Eli all things that I have spoken against his house: when I begin I will also make an end. For I have told him that I will judge his house forever for the iniquity which he knoweth, because his sons made themselves vile and he restrained them not; therefore I have sworn unto the house of Eli that the iniquity of Eli’s house shall not be purged with sacrifice nor offering forever.”

What was the sign of his doom? The same passage answers: “And this shall be a sign unto thee, that shall come upon thy two sons, on Hophni and Phinehas: in one day they shall die both of them. And I will raise me up a faithful priest, that shall do according to that which is in my heart and in my mind: and I will build him a sure house; and he shall walk before mine anointed forever. And it shall come to pass, that everyone that is left in thy house shall come and bow down to him for a piece of silver and a loaf of bread.” That was the sign. In the time of Solomon the priesthood goes back to the true line, in fulfilment of the declaration in that sign. The priesthood passes away from Eli’s descendants and goes back where it belongs, to Zadok – who is a descendant of Aaron’s eldest son.

The Philistine nation at this time dominated Israel. The word, “Philistines,” means emigrant people that go out from their native land, and it is of the same derivation as the word “Palestine.” That Holy Land, strangely enough, takes its name from the Philistines. The Philistines were descended from Mizraim, a child of Ham, and their place was in Egypt.

Leaving Egypt they became “Philistines,” that is, emigrants, and occupied all of that splendid lowland on the western and southwestern part of the Jewish territory, next to the Mediterranean Sea, which was as level as a plain, and as fertile as the Nile Valley. There they established five independent cities, which, like the Swiss Cantons, formed a confederacy. While each was independent for local affairs, they united in offensive and defensive alliances against other nations, and they had complete control of Southern Judea at this time. Joshua had overpowered them, but the conquest was not complete. They rose up from under his power, even in his time, and in the time of Samson and Eli they brought Israel into a pitiable subjection. They were not allowed to have even a grindstone. If they wanted to sharpen an ax they had to go and borrow a Philistine’s grindstone, and what a good text for a sermon! Woe to the man that has to sharpen the implement with which he works in the shop of an enemy! Woe to the Southern preacher that goes to a radical critic’s Seminary in order to sharpen his theological ax!

Speaking of the evils of a plurality of wives, we found Hannah in great bitterness of heart because she had no child, and we saw her lingering at the central place of worship, and without saying words out loud, her lips were moving, and her face was as one entranced, so that Eli thinks she is drunk. The New Testament tells us of a certain likeness between intoxication with ardent spirits and intoxication of the Holy Spirit. She told him that she was praying. When her child was born she came back and said to him, “I am the woman that you thought was drunk, but I was praying,” and then she uses this language: “I prayed for this child,” holding the little fellow up in her hands, “and I vowed that if God would give him to me I would lend him to the Lord all the days of his life,” and therefore she brings him to be consecrated perpetually to God’s service. The scripture brings all that out beautifully.

So the text speaks of the woes pronounced on a parent who put off praying for and restraining his children until they were grown. Like Hannah we should commence praying for them before they are born; pray for them in the cradle, and if we make any promise or vow to God for them, we should keep the vow.

I know a woman who had many children and kept praying that God would send her one preacher child, promising to do everything in her power to make him a great preacher. The Lord gave her two. One of my deacons used to send for me when a new baby was born, to pray for it. Oliver Wendell Holmes says a child’s education should commence with his grandmother. Paul tells us that this was so with Timothy. The Mosaic law required every male to appear before the Lord at the central place of worship three times a year. The text says that Elkanah went up yearly, but does not state how many times a year. The inference is fairly drawn that he strictly kept the Mosaic law.

Samuel had certain duties in the tabernacle. He slept in the Lord’s house and tended to the lights. It is a great pity when a child of darkness attends to the lights in God’s house. I heard a preacher say to a sexton, “How is it that you ring the bell to call others to heaven and you, yourself, seem going right down to hell?” And that same preacher said to a surveyor, “You survey land for other people to have a home, and have no home yourself.” So some preachers point out the boundaries of the home in heaven and make their own bed in hell.

Samuel’s call from God, his first prophecy, and his recognition by the people as a prophet are facts of great interest, and the lesson from his own failure to recognize at once the call is of great value. In the night he heard a voice saying, “Samuel! Samuel!” He thought it was Eli, and he went to Eli and said, “Here I am. You called me.” “No, I didn’t call you, my son; go back to bed.” The voice came again, “Samuel, Samuel,” and he got up and went to Eli and said, “You did call me. What do you want with me?” “No, my son, I did not call you; go back and lie down,” and the third time the voice came, “Samuel, Samuel,” and he went again to Eli. Then Eli knew that it was God who called him, and he said, “My son, it is the Lord. You go back and when the voice comes again, say, Speak, Lord; for thy servant heareth,” and so God spoke and the first burden of prophecy that he put upon the boy’s heart was to tell the doom of the house of Eli. Very soon after that all Israel recognized Samuel as a prophet of God.

The value of the lesson is this: We don’t always recognize the divine touch at first. Many a man under conviction does not at first understand its source and nature. Others, even after they are converted, are not sure they are converted. It is like the mover’s chickens that, after their legs were untied, would lie still, not realizing that they were free. The ligatures around their legs had cut off the circulation, and they felt as if they were tied after they were loose. There is always an interval between an event and the cognition of it. For example, when a shot is fired it precedes our recognition of it by either the sight of smoke or the sound of the explosion, for it takes both sound and sight some time to travel over the intervening space. I heard Major Penn say that the worst puzzle in his life was the experiences whereby God called him to quit his law work and become an evangelist. He didn’t understand it. It was like Samuel going to Eli.

I now will give an analysis of that gem of Hebrew poetry, Hannah’s song, showing its conception of God, and the reason of its imitation in the New Testament. The idea of Hannah’s conception of God thus appears:

There is none besides God; he stands alone. There is none holy but God. There is none that abaseth the proud and exalteth the lowly, feedeth the hungry, and maketh the full hungry, except God; and there is none but God that killeth and maketh alive. There is none but God who establisheth this earth; none but God who keepeth the feet of his saints; none but God that has true strength; none but God that judgeth the ends of the earth, and the chief excellency of it is the last: “He shall give strength unto his king and exalt the horn of His Anointed.” That is the first place in the Bible where the kingly office is mentioned in connection with the name “Anointed.” The name, “Anointed,” means Christ, the Messiah.

It is true that it was prophesied to Abraham that kings should be his descendants. It is true that Moses made provision for a king. It is true that in the book of Judges anointing is shown to be the method of setting apart to kingly office, but this is the first place in the Bible where the one anointed gets the name of the “Anointed One,” a king. Because of this messianic characteristic, Mary, when it was announced to her that she should be the mother of the Anointed King, pours out her soul in the Magnificat, imitating Hannah’s song.

The state of religion at this time was very low. We see from the closing of the book of Judges that at the feast of Shiloh they had irreligious dances. We see from the text here that Hophni and Phinehas, the priests of religion, were not only as corrupt as anybody, but leaders in corruption. We see it declared that there is no open vision, and it is further declared that the Word of God was precious – rare.

I will now explain these two phrases in the texts, 1 Samuel 1:16 (A. V.), where Hannah says, “Count not thine handmaid for a daughter of Belial,” and in 2:12 (A. V.), where Hophni and Phinehas are said to be the “sons of Belial.” The common version makes Belial a proper name; the revised version does not, and the revised version is at fault. If you will turn to 2 Corinthians 6:15, you will see that Belial is shown to be the name of Satan: “What concord hath Christ with Belial?” Get Milton’s Paradise Lost, First Book, and read the reference to Hophni and Phinehas as sons of Belial, and see that he correctly makes it a proper name.

Samuel was not a descendant of Aaron. He was merely a Levite, but he subsequently, as we shall learn, officiated in sacrifices as if he were a priest or high priest. It will be remember-ed that the priesthood was under the curse pronounced on Eli, and Samuel was a special exceptional appointee of God, as Moses was.

Dr. Burleson, a great Texas preacher, and a president of Baylor University, preached all over Texas a sermon on family government, taking his text from 1 Samuel 2:31.

There are some passages and quotations from Geikie’s Hours With the Bible on the evils of a plurality of wives that are pertinent. Commenting on Elkanah’s double marriage he says, “But, as might have been expected, this double marriage – a thing even then uncommon – did not add to his happiness, for even among the Orientals the misery of polygamy is proverbial. ‘From what I know,’ says one, ‘it is easier to live with two tigresses than with two wives.’ And a Persian poet is of well-nigh the same opinion: – “Be that man’s life immersed in gloom Who needs more wives than one: With one his cheeks retain their bloom, His voice a cheerful tone: These speak his honest heart at rest, And he and she are always blest. But when with two he seeks for joy, Together they his soul annoy; With two no sunbeam of delight Can make his day of misery bright.” An old Eastern Drama is no less explicit: – “Wretch I would’st thou have another wedded slave? Another? What? Another? At thy peril Presume to try the experiment: would’st thou not For that unconscionable, foul desire Be linked to misery? Sleepless nights, and days Of endless torment – still recurring sorrow Would be thy lot. Two wives! O never! Never! Thou hast not power to please two rival queens; Their tempers would destroy thee; sear thy brain; Thou canst not, Sultan, manage more than one. Even one may be beyond thy government!”

QUESTIONS

1. Why omit Part I of the textbook?

2. What, in bulk, is the supplemental matter in Chronicles, and what its importance?

3. What and where the place of Samuel’s birth, residence, and burial?

4. What his ancestry and tribe?

5. If he belonged to the tribe of Levi, why then is he called an Ephraimite, or Ephrathite, which in this place is equivalent?

6. Show that the bigamy of Samuel’s father produced the usual bitter fruit.

7. What was the attitude of the Mosaic law toward a plurality of wives, and divorce, and why?

8. Why did the law ever permit these things?

9. What is the bearing of this section of the contention of the radical critics that the Levitical part of the Mosaic law was not written by Moses, but by a priest in Ezekiel’s time, and that Israel had no central place of worship in the period of the Judges?

10. When did Shiloh become the central place of worship, how long did it so remain, and what use did Jeremiah make of its desolation?

11. Trace the subsequent and separate history of the ark of the covenant and the tabernacle, and show when and where another permanent central place and house of worship were established.

12. Who was high priest at Samuel’s birth, how was he descended from Aaron, and what the proof that he also judged Israel?

13. With which of the judges named in the book of Judges was he likely a contemporary?

14. What was Eli’s character, sin, doom, sign of the doom, and who announced it to him?

15. What nation at this time dominated Israel?

16. Give a brief and clear account of these people.

17. Show how Samuel was a child of prayer, the subject of a vow, a Nazarite, how consecrated to service, and the lessons therefrom.

18. How often did the Mosaic law require every male to appear before the Lord at the central place of worship, and to what extent was this law fulfilled by Samuel’s father and mother?

19. What were the duties of the child Samuel in the tabernacle?

20. Give an account of Samuel’s call from God, his first prophecy, his recognition by the people as a prophet, and the lesson from his own failure, for a while, to recognize the call.

21. Analyze that gem of Hebrew poetry, Hannah’s song, showing its conception of God, and give the reason of its imitation in the New Testament.

22. What was the state of religion at this time?

23. Explain the references to Belial in 1 Samuel 1:16; 2:12.

24. As Samuel was not a descendant of Aaron, but merely a Levite, why does he subsequently, as we shall learn, officiate in sacrifices as if he were a priest or high priest?

25. What great Texas preacher preached all over Texas a sermon on family government, taking his text from 1 Samuel 2:31?

26. Cite the passages and quotations from Geikie’s Hours With the Bible on the evils of a plurality of wives.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.