Description

THE ANCIENT

British and Irish Churches

INCLUDING

THE LIFE AND LABORS OF ST. PATRICK

BY

WILLIAM CATHCART, D. D.

Editor of The Baptist Encyclopaedia, and Author of The Papal System

WITH MAPS, ILLUSTRATIONS, AND FULL INDICES

PHILADELPHIA

CHARLES H. BANES

1420 Chestnut Street

1894

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1894, by the AMERICAN BAPTIST PUBLICATION SOCIETY,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C.

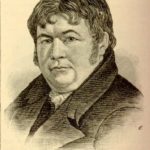

William Cathcart

PREFACE.

The inhabitants of England, Ireland, and Scotland, before the invasion of the Anglo-Saxons in the fifth century, had common Celtic ancestors. There is no more interesting or less known portion of ecclesiastical history than that of the ancient religious communities of Great Britain and Ireland. Not one of these powerful churches was founded by Rome or rendered any allegiance to the supreme pontiff for centuries after its establishment.

The Britons were evangelized before the end of the fourth century. Their scanty religious history inspires admiration for their heroism under imperial Roman, and heathen Anglo-Saxon persecutions, and deep regret that so few of their ancient records were spared. St. Patrick, Ninian, and Kentigern, the apostles of great numbers of converts, were Britons. Helena, the Christian mother of Constantine the Great, was a native of Britain. No people in Christian history ever showed greater fidelity to their Bible principles, when sacerdotal enemies of the gospel tried to drive them from the truth.

St. Patrick’s career as a slave, as a prince of preachers, as a missionary, who by Divine help overcame the fierce idolatry of a whole nation, and by his unselfish love captured their hearts and those of their descendants for fourteen hundred and fifty years, is without an exact parallel in all the biographies of missionary heroes. His Christian life is full of fascination.

William Cathcart

The history of Patrick began to lose its legendary character after the learned Archbishop Ussher, in the seventeenth century, showed him to the world as a simple and mighty evangelical preacher, like the illustrious primate of Ireland himself. George III., in 1783, established for Ireland its only order of knighthood, the knights of St. Patrick. George was a very decided Protestant. Neither he nor his ministry had any purpose to conciliate Roman Catholics in the new institution. The Irish Parliament was a Protestant body; and a majority of the knights have always been Protestants.

The great Protestant “Religious Tract Society” of London, the mother of all similar organizations everywhere, has issued within a few years the works of St. Patrick in its series called “Christian Classics,” which contains one each of the productions of St. Augustine, Anselm, Athanasius, Basil, and William Tyndale, the illustrious translator of the English Bible.

William Cathcart

The “Lords Commissioners” of the British Treasury, in 1887, ordered that “The Tripartite Life of Patrick,” with other documents relating to that saint, should be printed and placed among the “chronicles and memorials of Great Britain and Ireland during the middle ages.” This learned publication is an encyclopaedia of ancient writings relating to Patrick, and of his own genuine works.

The volume which we now send forth, contains careful translations of Patrick’s extant literary efforts, and an account of every known and important transaction of his life. It also furnishes sketches of the labors of Ninian and Kentigern in Scotland, and of the life and labors of Columba, the apostle of the Northern Picts of Caledonia, probably the greatest Irishman who ever served the Saviour.

It relates the wonderful story of the Hibernian mission from Iona to the pagan Anglo-Saxons, presided over by Aidan, Finan, and Colman, which, by the grace of God, resulted in the conversion of at least two thirds of that people, whose descendants to-day own so much of the wealth, commerce, territory, power, and missionary enterprise of the world. Augustine, the Italian Archbishop of Canterbury, and his fellow-monks, were little more than pioneers in the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons. This glorious Hibernian success rests upon evidence as strong as that which makes it certain that William the Conqueror gained the victory over Harold at the battle of Hastings.

William Cathcart

It presents historical testimony showing that the ancient Britons, Picts, and Hibernians were not Roman Catholics. It treats of the marriage of the British and Irish clergy, and of their great monastic institutions, which were established as missionary societies, theological seminaries, Bible copying and distributing organizations, as parsonages for great numbers of home missionaries, and as universities, divinely favored in imparting a learned education to semi-barbarous Anglo-Saxons, and to unenlightened youths from every quarter of Europe.

It describes a number of the leading doctrines and observances of the ancient British and Irish churches, based upon their early commentaries or other writings, which show a remarkable agreement with the creeds and practices of the evangelical Christians of our day, but especially with those of the Baptists.

William Cathcart

The story is one of the greatest interest, and entirely controverts the claims of the Homan hierarchy respecting these ancient Christians and the foundations they established.

Foot-notes furnish reliable authorities for all the important statements that are made. I am indebted to the Rev. Philip L. Jones, A. B., for valuable suggestions.

William Cathcart

Philadelphia, Jan., 1891.

Ancient British and Irish Churches.

BOOK I. CHRISTIANITY AMONG THE ANCIENT BRITONS.

CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION OF CHRISTIANITY. William Cathcart

Dean Stanley and Augustine-The Anglo-Saxons not chiefly evangelized by Romish missionaries—Roman legions—Roman traders

Commerce with the East-Greeks and Marseilles-Persecutions at Vienne and Lyons-Simon Zelotes, Paul, Peter, Philip, and others, supposed to have been missionaries in Britain.

The ancient Britons, who once occupied all England and a considerable part of Scotland, had much to do, through their religious descendants, in the conversion of their Anglo-Saxon conquerors. These pagans, coming into Britain m the fifth century, reared temples of idolatry in all directions, an destroyed every vestige of British Christianity within their reach. In A. d. 596, Gregory the Great, bishop of Rome, a man of large heart and of sincere piety, sent a company о missionaries into Britain to seek the salvation of the heathen Anglo-Saxons. At the head of this band was Augustine, the first” archbishop of Canterbury. This prelate had some vanity, a limited measure of true religion, a good master in Gregory, and favoring circumstances.

The late Dean Stanley, while a canon of Canterbury, wrote:

I have said little of Augustine himself, and that First, because so little is known of him; secondly because I must confess, that what little is told of him leaves an unfavorable impression behind. “We cannot doubt that he was an active, self-denying man—his coming here through so many dangers of sea and land proves it; and it would be ungrateful and ungenerous not to acknowledge how much we owe to him. But still, almost every personal trait which is recorded of him shows that he was not a man of any great elevation of character, that he was thinking of himself, or of his order, when we should have wished him to be thinking of the great cause he had in hand. We see this in his drawing back from his journey to Britain in France; we see it in the additional power which he claimed from Gregory over his companions ; we see it in the warnings sent to him by Gregory that he was not to be puffed up by the wonders he had wrought in Britain ; we see it in the haughty severity with which he treated the remnant of British Christians in Wales, not rising when they approached, and uttering that malediction against them, which sanctioned, if it did not instigate, their massacre by the Saxons.[i]

William Cathcart

The success of Augustine of Canterbury, during his life, was not very extensive. Laurence, who followed him in that see, after the death of Ethelbert, met with serious trouble. His son Eadbald[ii] refused the faith of Christ, and fell into immorality. “By these offenses,” Bede says, “he gave occasion to those to return to their former uncleanness, who, under his father, had, either for favor or through fear of the king, submitted to the laws of faith and chastity.” And such was the extent of this apostasy that Laurentius concluded to leave Britain, and was only hindered by what he represented as a miraculous visit of St. Peter, who gave him good advice and a sound “scourging,” which lasted “for a long time.” The same thing occurred among the East Saxons. The three sons of Sabert, the king, professed idolatry after his death, and the people turned to their old idols with renewed devotion; and Mellitus, their bishop, with Justus, bishop of Rochester in Kent, fled to France, these two bishops and Laurentius having “unanimously agreed that it was better for them all to return to their own country, where they might serve God in freedom, than to continue without any advantage among these barbarians who had revolted from the faith.”

Paulinus, probably the ablest and best of the Italian missionaries, labored with much apparent success in the kingdom of Northumbria from a. d. 625 to A. d. 633, when there was a great slaughter of Christians in Northumbria, and flight alone promised safety; Paulinus removed to Kent, and became bishop of Rochester, where he lived for nineteen years, having completely abandoned his work[iii] in that region.

William Cathcart

These forsaken fields were reclaimed and others were occupied, partly by those who fled from their flocks, but chiefly by the Scottish missionaries, the religious descendants of St. Patrick, without whose glorious labors, in all probability, the Anglo-Saxons would have been largely pagans for centuries.

William Cathcart

The ancient Britons belonged to the great Celtic race, sections of which furnished inhabitants to Great Britain and Ireland, and to Gaul long before its conquest by the Franks. The Britons had nothing in common with the Anglo-Saxons. In religion they followed Druidism; private quarrels were judged by their priests, as well as disputes about bequests, and all criminal accusations. Punishments and rewards were controlled by them; they exercised the greatest power over the public and private lives of the people. They used their whole authority against the Roman invaders of Britain, who found it necessary to destroy them. Under Suetonius Paulinus, the legions in Britain overthrew the altars and destroyed the ancient forests, until, in Nero’s time, Druidism was shut up within the little island of Mona (Anglesey). Thither it was followed by Suetonius Paulinus. In vain the sacred virgins hurried to the shore like furies, in mourning habits, with disheveled hair, and brandishing torches. He forced the passage, and slaughtered every human being that fell into his hands. This occurred in a. d. 61.[iv] The sacred groves of the Druids were cut down, and all traces of their former authority removed. From this crushing blow Druidism never recovered. Its overthrow in South Britain banished the Saviour’s greatest enemy.

It is impossible to fix the exact date when the gospel was first introduced into Britain; nor can the channels through which it came be determined with certainty. As the first preachers of the gospel in Rome are wholly unknown, so the records of men furnish nothing reliable about the first British missionaries.

William Cathcart

The Roman legions and colonists were likely to bring some of the persons who first told the story of the cross in Britain. Roman legions were located for an indefinite period in some one country—a century, or even centuries; they were never recruited in the province where they were encamped, but in foreign and often distant countries. An English legion might have as recruits some of Paul’s converts in Asia Minor. British recruits might be sent to some legion located in the East, and might be converted there. And they, on their final return home, and foreign disciples serving Rome in Britain, would surely aid in spreading the gospel in that country.

The conversion of Cornelius, of the Italian band in Caesarea, under Peter’s ministry, was one of many cases where an officer and his household were fitted by forgiveness to tell those around them at the time and on their return to their old homes, their former neighbors and friends, the power of the Crucified to take away sin. Through this agency, doubtless, many Britons were saved.

The Roman legions in Britain needed much which it could not furnish. Early after the Saviour’s death, Roman traders followed the legions to supply their wants, and to sell the natives the products of other lands. Toward the close of the first century, when Agricola completed the subjugation of the Britons, he encouraged them to build temples and houses, and to imitate the dress and luxuries of their conquerors. From A. d. 84, they gradually adopted Roman usages.[v] These new tastes, and the wants of the army, brought many Roman civilians into Britain, among whom or their families it is probable that there were Christians, whose light would reach the hearts of their British neighbors.

William Cathcart

Never in the history of our race was there a zeal that surpassed that of the early Christians. Maligned, tortured, destroyed, by Nero and others, nothing could silence them. The world had not dangers with sufficient force to stop their efforts and sacrifices to save souls; and somehow they reached Britain to tell the story of Christ’s love. There is reason to believe that the gospel came to Britain chiefly in the track of commerce. The Tyrians traded with Britain for ages before the Christian era. The Carthagenians, after the capture of Tyre by Alexander the Great, inherited for a time the commerce of Britain.

The Greeks, first as rivals, and then as successors to the Carthagenians, took possession of the exports and imports of Britain. Marseilles, a Greek colony in France, said to have been founded five hundred years before Christ, was the grand depot to which the tin, lead, and skins of Britain were conveyed, and from which they were transported to all parts of the world with which the Greeks had commercial relations.[vi] The conversion of many Greeks in early Christian times accomplished much for the spread of the gospel, and even through business relations that intelligent and resolute people sometimes rendered great service in extending Christ’s kingdom.

Two young men were taken by Meropius, a Greek of Tyre, to Abyssinia about a. d. 331; upon his death in that land, whither he had gone as a traveler, they unexpectedly found themselves favorites of one of its kings, holding important appointments. One of them, Frumentius, built a house of prayer, and afterward was appointed a bishop through the famous Athanasius. Socrates, the historian, states that he was a successful missionary.[vii] We have reason to believe that Greek Christians buying tin and lead compassionated the idolatrous Britons who exported these scarce metals, and preached Christ to them.

William Cathcart

The first known church in France was founded by Greeks. In A.d. 177, the Christians of Vienne and Lyonswere dragged into cruel notoriety by savage persecutions borne with heroic fidelity. Milman states that these Christians appear to have been a religious colony from Asia Minor, or Phrygia. Pothinus, their bishop, was in his ninetieth year when dragged to prison, from the barbarities of which in two days he ascended to heaven. His name showed his Greek origin. When the persecution ended, surviving Christians wrote an account of the fiendish sufferings inflicted upon their martyrs to their Phrygian brethren.[viii] The sketch covers eleven octavo pages, and it is given entire by Eusebius.[ix] It is full of the grace of God, and of the most touching recitals that ever shocked human hearts. The writers have nothing to say to Pope Eleutherius in this document; they are Greeks and disciples whom they have made, and they send this record of the sufferings of tbeir tortured and slain brethren and sisters to their fellow-believers in Asia Minor.

Greek Christians in France or in the East, it is believed, long before a.d. 177, when persecution gave European and Asiatic prominence to the churches of Lyons and Vienne, gave effective help to the evangelization of Britain. Neander expresses a common opinion about the origin of British Christianity when he says:

A later tradition of the eighth century reports that Lucius, a British king, requested the Eoman bishop, Eleutherius, in the latter part of the second century, to send him some missionaries. But the peculiarity of the later British church is evidence against its origin from Rome. For in many ritual matters it departed from the usage of the church of Rome, and agreed much more nearly with the churches of Asia Minor. It withstood for a long time the authority of the Romish papacy. This circumstance would seem to indicate that the Britons had received their Christianity either immediately, or through Gaul, from Asia Minor; a thing quite possible and easy by means of the commercial intercourse. The later Anglo-Saxons, who opposed the spirit of ecclesiastical independence among the Britons and endeavored to establish the church supremacy of Rome, were uniformly inclined to trace back the church establishments to a Roman origin; from which effort many false legends, as well as this, might have arisen.[x]

William Cathcart

Fox gives the same common impression about the East furnishing the first laborers in Britain: “By all which conjectures it may stand probably to be thought that the Britons were taught first by the Grecians of the East church rather than by the Romans.”[xi] Fox mentions Joseph of Arimathea, who was sent from Gaul into Britain with twelve others, by the Apostle Philip about A.d. 63, who spent the remainder of his life in that country wTith his companions, and laid the foundations of the Christian church in it. He states also that Simon Zelotes was reported to have brought the gospel of Christ to Britain. The Apostle Paul has been claimed as the founder of British Christianity, and the learned Stillingfleet,[xii] while failing to establish his title to this signal addition to many kindred honors, comes very near to success. Philip, the apostle, has been represented as one of the early, if not the first, preachers of the gospel in Britain. The Apostle Peter is also heralded as a preacher in Britain. James, the son of Zebedee, is also in the list of British missionaries. Aristobulus, of whom Paul speaks in Rom. 16: 10, appears as one of the Saviour’s reputed heralds to the ancient Britons. Surely such an array of apostles, supposed to be preachers in Britain, is, at least, evidence of the general conviction that the Christianity of that land is from the East, either directly, or through France.

Mosbeim says:

Whether any apostle, or any companion of an apostle, ever visited Britain, cannot be determined; yet the balance of probability rather inclines toward the affirmative. The story of Joseph of Arimathea might arise from the arrival of some Christian teacher from Gaul, in the second century, whose name was Joseph. As the Gauls, from Dionysius, bishop of Paris in the third century, made Dionysius the Areopagite to be their apostle; and the Germans made Maternus, Eucherius, and Valerius, who lived in the third and fourth centuries, to be preachers of the first century and attendants on St. Peter; so the British monks, I have no doubt, made a certain Joseph from Gaul, in the second century, to be Joseph of Arimathea.[xiii]

There is no reliable evidence that any of the apostles, or their companions, ever preached in Britain.

William Cathcart

[i] “Historical Memorials of Canterbury,” pp. 33, 34. London, 1855.

[ii] Bede’s “Eccles. HistLib. II., cap. 5, G.

[iii] Bede’s “Eccles. Hist.,” Lib. II., cap. 21.

[iv] “Tacit. Annal., ” XIV., 29, 30.

[v] Tacit. “ Vit. Agr.,” cap. 21.

[vi] Thackeray’s “Researches into the Ecclesiastical and Political State of Ancient Britain,” Vol. I., p. 18. London, 1843.

[vii] “Eccles. Hist.,” Lib. I., cap. 19.

[viii] “History of Christianity,” p. 256. New York.

[ix] “Eccles. Hist.,” Lib. V., cap. 1.

[x] “General History of the Christian Church,” Vol. I., pp. 85, 86. Boston.

[xi] “Acts and Monuments,” I., 306, 307. London, 1847.

[xii] “The Antiquities of the British Churches,” p. 39. London, 1840.

[xiii] Mosheim’s “Eccles. Hist.,” p. 52. Loudon, 1848.

William Cathcart

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.